This article is free to redistribute under Creative Commons. By Nick Bilton

Earlier this year I was invited with a good friend and colleague to speak at somewhat secret conference in Toronto—we didn’t know it was hush-hush at the time. The event was invite only, and my friend and I didn’t have much knowledge of who specifically we were going to be presenting to, just that it was to be ‘world technology leaders from both the private and government sector’.

‘Sure, Toronto for a day, that’d be fun!’

When we arrived and registered we were given the typical badges with our first names and company’s title and we sat in to hear the days speakers. As I looked at the conference materials, I noticed, along with the typical big-boy companies like GE, IBM, Apple etc. there were also a lot of 3 letter acronyms behind the names of some of the attendants; FBI, CIA, EPA, NSA and so on. Ok, I thought, nothing to worry about here, I’m a guest. Right?

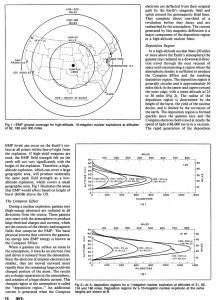

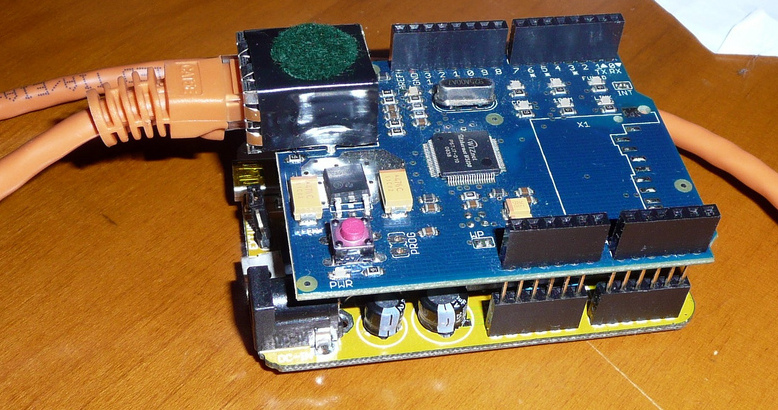

Most of the talks were by technologists & CTO’s discussing projects they are working on in robotics, geo-location, and future mobile devices. There were a couple of digital artists thrown in there, and a living cyborg discussing life as a ‘robot’. On day 2, an older gentleman got up to present, and a quick glance at his bio showed that he was a former director, now retired, of one of those government run 3-letter acronyms I mentioned earlier. My ears perked up as I thought maybe he’d tell us about Area 51 or who really killed JFK, but instead he gave a really interesting talk about Amateur Radio operators (HAMs). His talk was very technical, discussing the properties and divergent layers of the ionosphere and the design specifications needed to build antennas that could broadcast to someone on the other side of the world, just by bouncing the radio waves off different levels of the atmosphere. A majority of it was beyond my technical understanding, but his talk was alluring. One topic he discussed toward the end, albeit rather generally, was that HAM radios are one of the very few forms of communications that would still work during a national disaster, he went on to say that if someone managed to explode an EMP (Electro Magnetic Pulse) at a certain elevation above the USA that our entire infrastructure could go down, cell phones, internet (gasp!), banking etc. but that HAM radios, with their low power and ability to communicate on simplex networks (radio to radio) would still work.

When I returned to New York I decided to do a little research into some of the material the speaker presented and among the tremendous amount of content about HAMs I found a paper written by the National Communications System in Washington DC, the paper was titled “Electromagnetic Pulse and the Radio Amateur” and was written in August, 1986, over 20 years ago. Although the paper was old and extremely technical, talking about nuclear electric pulses and things that, thankfully, never ended up happening during the cold war, it opened up discussing the importance of the Amateur Radio Operators to ‘assist in national disasters, tornadoes, floods, blizzards… power outages, and nearly all emergency disaster relief’.

Diving a little further, and closer to today, I found out that HAMs were an integral part of the rescue operation during Katrina. When the government was missing and the cell networks were down, and power completely non existent throughout New Orleans, HAM operators went out in search of stranded families, notifying the coast guard and volunteer rescuers, via HAM radio, of the location of marooned citizens. HAMs helped coordinate during both recent black outs in New York, and were integral during 9-11. During all these national emergencies, when the cellular networks and internet routes was inaccessible, HAM Radios and battery powered repeaters were in full operation.

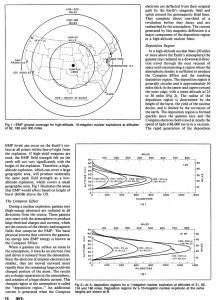

Earlier in the year a friend showed up to an NYCResistor meeting with his HAM radio and as he explained how the radios worked, we sat there listening to the aviation and police scanners (which are both legal to listen to in NYC if you are a licensed HAM) and he chatted with other radio operators. Then a few weeks later, my friend Diana Eng and I decided to download some online study guides and take the test, which we both passed (although I had to take it twice) and I am now an FCC licensed Amateur Radio Operator. I haven’t saved the world or thwarted any national emergencies yet (despite the fact that I have daydreamed about it) but I have talked to other HAMs, listened to the emergency scanners in my neighborhood, and my friends Dave, Will and Diana have built a new antenna so we can talk to satellites, and possibly even astronauts (who are all required to get their HAM license before going into space). Since then, I’ve also found out that I know quiet a few other licensed HAMs.

Some coworkers and friends have laughed when I gleefully announce that I got my license. The common response has been ‘why would you do that? You can just talk to someone on instant messenger or Twitter’, or ‘an EMP will never happen in the USA, are you going to build an air-raid shelter too?’. Maybe they’re right, maybe I’m just being dramatic, but I remember during the last blackout in New York it took hours before anyone knew what was happening, and with no access to reliable news sources, rumors were flying rampant about terrorist attacks, alien invaders and the Mayan calendar.

Something tells me, when the lights go out again in New York, which they will, or during the next national disaster, the same people who jest with me now, will be wishing they had their HAM radio license too.